aec-membership-test-simulator

AEC Party Membership Test Methodology is Rigged! A Statistical Analysis of AEC Methodology and Graphs (of PMFs)

Website

|

Source Code

Max Kaye

2022-02-15 to 2022-02-21

TOC

- Background Context

- Regular Membership Testing

- Flux’s 2021 Membership Test: A Known Farce

- Analysis Methodology

- Major Findings

- Suspected Farces

- Flux’s 2021 Membership Test Assuming a Threshold (9.09%) Denial Rate (including worst-case)

- Flux’s Second Membership Test (March 2022)

- Feedback Loops Between AEC Policy and Party Behavior

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Definitions

- Appendix: AEC Membership Testing Tables

- Appendix: Errata

Abstract / Executive Summary

In Australia, to register a political party you need a minimum number of members. Federally, that’s usually 1500 (as of September 2021) – the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) will conduct membership tests to verify this minimum. Political parties with a parliamentarian have no minimum membership limit and are not tested. Political parties without a parliamentarian must go through a membership test when they register, and then once every election cycle thereafter.

This document evaluates the AEC’s testing methodology for particular cases and finds that there are real-world situations where the testing methodology has a false negative (improper failure) rate over 50%, and often much higher.

Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude, for those cases: the methodology is rigged and a farce.

If something is rigged and a farce – based on the definitions included and cited in the appendix – then it is an unfair, empty act, done for show where the outcome is already known. This document proves that the current method has unfair and predetermined outcomes for many situations.

Note: I am not accusing the AEC of doing the rigging; just proving that the method is rigged.

To date, there is 1 known incident of a farce, at least 7 suspected incidents, and at least 5 other possible farces. This is based only on results that the AEC have published as part of a review (other results are not available).

The Flux Party’s recent 2021 membership test is analyzed in multiple ways:

- Measured case: a 17% membership denial rate – as measured by the AEC during this membership test.

- More extreme – but realistic – cases: These are more extreme cases than the measured case, but it is an assumption of all cases that the party is eligible under the Electoral Act.

- Threshold case: the case where 9.09% (150/1650) of any membership list submitted will deny membership. I suspect this is close to an AEC assumption used for calculating the maximum number of denials for the AEC’s testing table (given their advertised risk of false results).

Experimental evidence shows that the measured true positive rate of The Flux Party’s 2021 membership test was just 28.3% ± 0.12%. This is despite the experimental assumption that Flux has more members than the legislatively required number.

In Flux’s threshold case, where 150/1650 = 9.09% of the submitted membership list will deny membership and 24 members are filtered without replacement, experimental evidence shows that the AEC method’s true positive rate was 89.0%, which is less than the limit previously advertised (90% or better). The true positive rate is that high because Flux has gone to a great deal of effort to increase the quality of our membership lists to avoid members being filtered – we did this, in large part, to address inadequacies of the AEC’s methodology. As more members are filtered without replacement, the false negative rate increases dramatically.

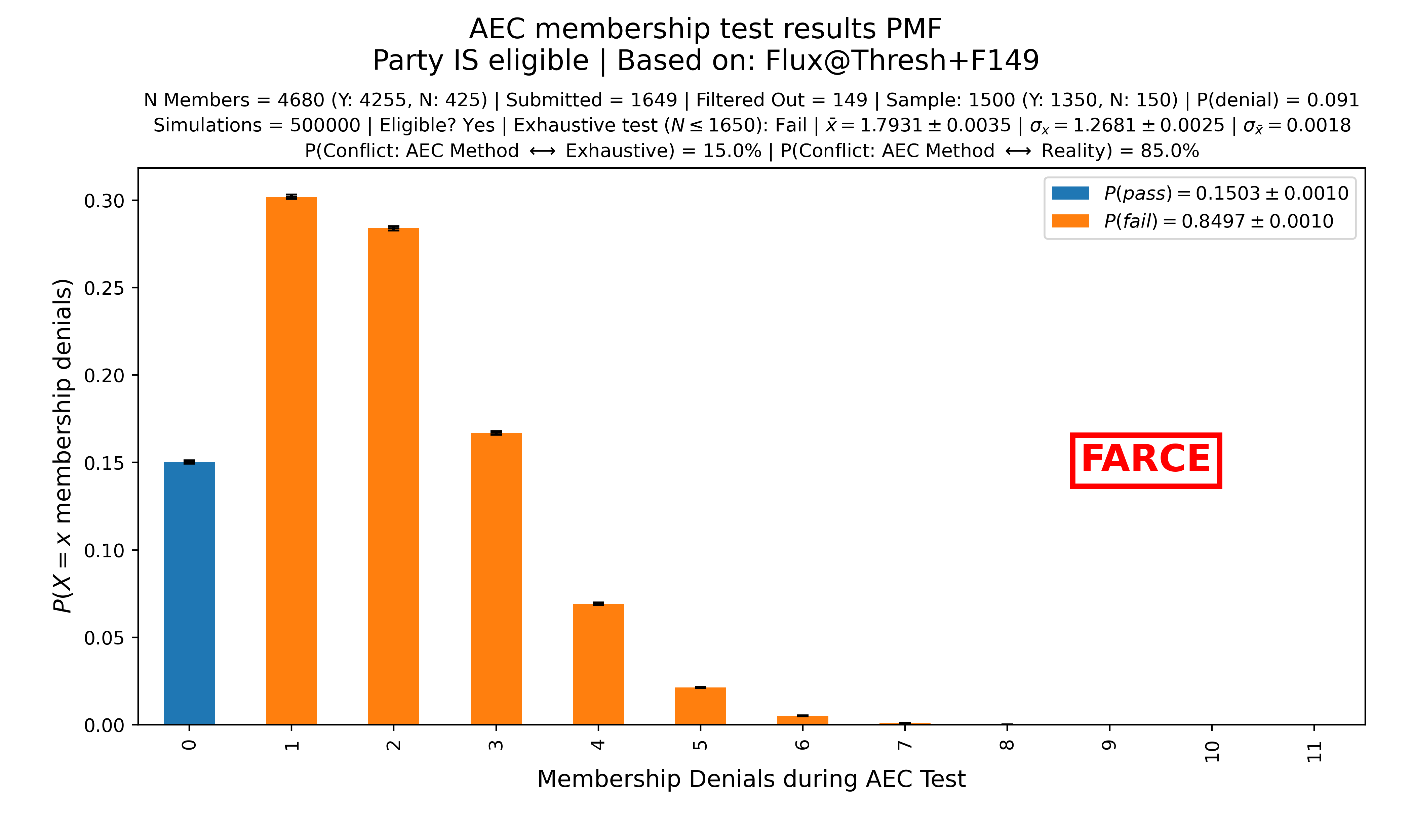

Experimental evidence proves that the AEC’s claim that their membership tests are 90% accurate is false. In actual fact, for a party that is capable of providing a list of 1,650 members wherein exactly 1,500 members will not deny membership (and 150 will): the worst-case accuracy of the AEC’s membership test is just 15.1%, indicating a false negative rate of 84.9%.

In other cases, where a party is capable of providing 1,500 members that will not deny membership (with no limit on the number of members that will deny membership), the lower-bound on the accuracy of the AEC’s method is 0%. That is: it fails 100% of the time for certain eligible parties.

This is not a theoretical problem. It has been happening and continues to happen. The AEC has been enforcing a policy that compromises the integrity of our political process. The ABS has been complicit. Political elites have exploited this.

Additionally, the AEC mistakenly enforced a testing table with a typo for 4 years – it’s unknown if they ever noticed before the table was updated. (See Appendix: AEC Membership Testing Tables / Circa 2012 to 2016)

Disclosure and context: My roles in The Flux Party (Flux) were: a founder, the deputy leader, the secretary, and the deputy registered officer.

Change Log

2022-04-11

Update: Flux was deregistered on 2022-03-24. See 8. Flux’s Second Membership Test (March 2022).

2022-04-14

Added Health Australia Party’s deregistration on 2022-04-05 to the list of suspected farces.

2022-04-16

Added affirmation of deregistration of Consumer Rights & No-Tolls on 2018-08-30 to the list of suspected farces.

2022-08-11

019ac4f Fixed quote typo (errant character) and linked LEX3132. (Relevant to section 8)

1. Background Context

Recently (leading up to September 2021), most parliamentarians (i.e., the 4 major parties) decided that we had too many political parties and that this was a problem! It would not do. So, a bunch of changes were made to the Electoral Act. Changes designed to make life harder for anyone who wanted to be part of our democracy, but did not want to participate in the rotten, tribalist, political cults that run the show. Some of those changes resulted in (as of Feb 2022) the pending deregistration of 12 parties, and the very real deregistration of 9 parties. In practice that is ~40% of parties, gone before the next election. Political elites will claim (and have claimed in Parliament already) that these changes, the culling, and the subsequent entrenchment of the status quo, is a good thing. That it is making our democracy better.

In September 2021, the legislatively required number of members for a political party was increased from 500 to 1500 with little warning and no grace period. The AEC’s policies – going back at least a decade – have encouraged parties not to bother going over 1.1x the legislative limit (i.e., previously 550, now 1650) with regards to their number of members that are verifiable against the roll. (Submitting more than this is pointless and makes registration harder.)

2. Regular Membership Testing

Every few years, the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) will check that each political party has enough members according to the legislative requirement. The party must provide a list of 1500 to 1650 names (inclusive) to use as evidence of their eligibility. The AEC will then filter out some names (duplicates, deceased members, etc). That produces a NEW list of ≤ 1650 names. Then, the AEC will do a statistical sampling of members and will use that to determine whether a party is eligible. Particularly, a small subset of members are selected and contacted, asking for a yes/no confirmation of membership. Non-responses are skipped. A “No” answer counts as a failure – this is a membership denial. In this document and associated code: “failure rate” refers to the rate at which members respond “No”.

The AEC does not accept lists larger than 1650; there is no chance for a party to replace any of those filtered members; that filtering process increases the chance of false negatives (when list length is limited + excluding duplicates); parties are not told which members were filtered (even those which are deceased) so they cannot be proactively removed; and, finally, the standard of statistical evaluation is to assume that the list of 1650 members were the only members of the party. Zero consideration is given beyond this, outside the chance to respond – a tactic that has, historically, performed poorly except by the grace of the AEC. How many parties have been wrongly denied registration due to this artificial limit? Nobody knows.

The method is detailed on pages 23 and 24 of “Guide for registering a party”. (mirror)

3. Flux’s 2021 Membership Test: A Known Farce

Flux failed its recent membership test. The only problem? We have at least 4680 members whose details have been matched against the electoral roll. It is the AEC’s imposition of 1650 members maximum that is the problem.

Note that Flux is only in a position to offer so many members because of our unique membership system: free for life. Additionally, significant automation has been developed to assist members in verifying their details against the electoral roll and keeping their details up to date. This is a task too involved, expensive, and specialized for it to be practical for most political parties.

From the AEC’s notice (note that the AEC refuses membership lists with more than 1650 members):

On 7 December 2021, the Party responded to the s 138A Notice by providing a list of between 1,500 and 1,650 members of the Party.

I am notifying you under s 137(1)(b) of the Electoral Act that the Electoral Commission is considering deregistering the Party, as the Electoral Commission is satisfied on reasonable grounds that the Party does not have at least 1,500 members. A copy of the s 137(1)(b) Notice is enclosed.

Here is an except from the first page of our response, to give you an idea of the gist:

We have 3 arguments supporting our case. Each argument is individually sufficient to show that a decision (by the AEC) to deregister the Party would not be based on reasonable grounds; each argument is a decisive criticism of the current methodology.

- The statistical method used fails ~10% of the time for borderline cases.

- The statistical method uses an artificially limited sample size and thus does not estimate party membership, though does (roughly) measure membership attrition.

- We have sufficient membership and provide evidence. Attached is a list of 4680 members. Each entry was, at some point, verified against the electoral roll.

Unless each of these criticisms can be addressed, we do not believe that a decision by the AEC to deregister the Party would be based in reality.

(Note: there are at least two non-critical errors in our response – the AEC has already been informed. See the end of the doc for what was sent to the AEC re those errors.)

I became curious about the actual statistical properties of the AEC’s process. How likely would it have been for us to succeed? (Given that we are in fact an eligible party.)

Turns out there was a 71.7% chance that the AEC’s method would find a false negative.

TL;DR: It’s rigged.

In this document and the associated code and graphs: a farce is defined as any case where the chance of a false negative is ≥ 50%, i.e., statistical accuracy is ≤ 50%.

The AEC’s membership test being rigged means that, in some relevant cases, the outcome is predetermined. Since there are cases where an eligible party will have ~0% chance of success, it is the case that there exist relevant cases where the outcome is predetermined.

4. Analysis Methodology

The code associated with this document produces statistical graphs (of the Probability Mass Function, specifically) based on 500,000 simulations of the AEC’s method.

For each simulation, the number of failures is recorded as the output. Subsequently, these results are normalized to give the probability of X failures for the given input parameters.

These probabilities are then graphed, with the x-axis showing the number of failures, and the y-axis showing – i.e., the probability of a membership test having a certain number of failures (membership denials).

As the AEC has limits on the acceptable number of membership denials based on the reduced membership list, the bars in these PMFs are colored blue or orange to indicate a pass or a failure. In cases where the party does meet legislative requirements, the blue bars (P(success)) should, according to AEC Policy, always sum to > 0.9. Where P(success) < 0.5, the case is deemed a farce and marked as such.

The simulation is initialized with a membership list – a list of N members where each member has a failure_rate chance (e.g., 0.0909) of responding “No” (i.e., a membership denial).

Each simulation proceeds thus:

- Randomly sample, without replacement,

sample_sizemany members from a party’s membership list.sample_sizeis the maximum allowable by the AEC. - Filter out

n_members_removedmany members (e.g., 24 members were filtered out of Flux’s 2021 membership test). This results in the “reduced membership list” mentioned above. - Randomly sample, without replacement,

n_to_samplemany members from the reduced membership list.n_to_sampleis based on the AEC’s published tables of sample sizes and the acceptable number of denials (these are dependant on the size of the reduced membership list). - Count the number of failing members and record as a result.

The results are compared against:

- AEC published accuracy claims

- Reality (will an eligible party fail the AEC’s test, or an ineligible party pass it?)

Note: after the main body of this paper, there is Appendix: AEC Membership Testing Tables which measures the accuracy of published AEC membership testing tables.

Running this simulator

If you want to skip this section, go to: 5. Major Findings.

Tested w/ python 3.9 and 3.10. (3.8 did not work.)

Install python3 deps: pip3 install -r requirements.txt or pip3 install matplotlib pandas click scipy

For the program’s arguments, run ./main.py --help (or python3 main.py --help).

You can find the (source code) in this paper’s repository.

Individual simulations are added in the aec() function.

The primary parameters of each simulation are: number of trials in the simulation, the population size of members from which the party can choose a membership list to provide, the failure rate of members confirming their membership when contacted, and the number of members that are filtered out of the list (reasons include: they support the registration of another party, they’re deceased, the details cannot be matched against the electoral roll, or duplicate entries).

Optionally, a specific AEC testing policy can be specified, along with different filtering methods.

Tables of chance of 1 success vs tests required are generated via calc-n-trials-required.py.

Main Simulator Loop

If you want to skip this section, go to: 5. Major Findings.

This is the main loop of the simulation. It has been run 500,000 times per graph unless otherwise mentioned.

# take sample from full membership list (which can be more that 1650 / the AEC's limit)

# the sample size is, at most, the legislative limit (e.g., 1650)

membership_sample = sample_from(members, sample_size, replace=False, shuffle=True)

# remove n_members_removed from the party list (these are filtered members).

# If `filter_any == False` then only members that will respond "yes" will be removed (this

# is the worst case for the party).

# - note: this usually makes little-to-no difference

# - members can be removed b/c their details couldn't be matched, they're deceased, or b/c

# they've supported another party's rego.

# - we usually want to remove true members to measure worst case performance of methodology.

# why?

# - if the party has excess members, then filtered members *could* be replaced with other

# valid members

# - if the party had a way to pro-actively filter these members out, the party would

# (so as to submit a higher quality list)

# - because that's what happens in a griefing attack (your fake-members will be sure not to

# give you bad details).

# - since there is no way to detect this and it is not random or uniformly distributed, it

# must be assumed.

if not filter_any:

reduced_sample = list(filter_out_n_members(

lambda m: m,

membership_sample,

n_members_removed))

else:

# the following line will remove n_members_removed indiscriminantly since

# `membership_sample` is shuffled.

# note: it makes little difference -- only in borderline cases.

reduced_sample = membership_sample[n_members_removed:]

assert reduced_sample_size == len(reduced_sample)

# perform check (contact member to confirm)

actual_sample = sample_from(reduced_sample, n_to_sample, replace=False, shuffle=True)

# count failures

n_failures = sum(0 if m else 1 for m in actual_sample)

# record results

results.append(n_failures)

5. Major Findings

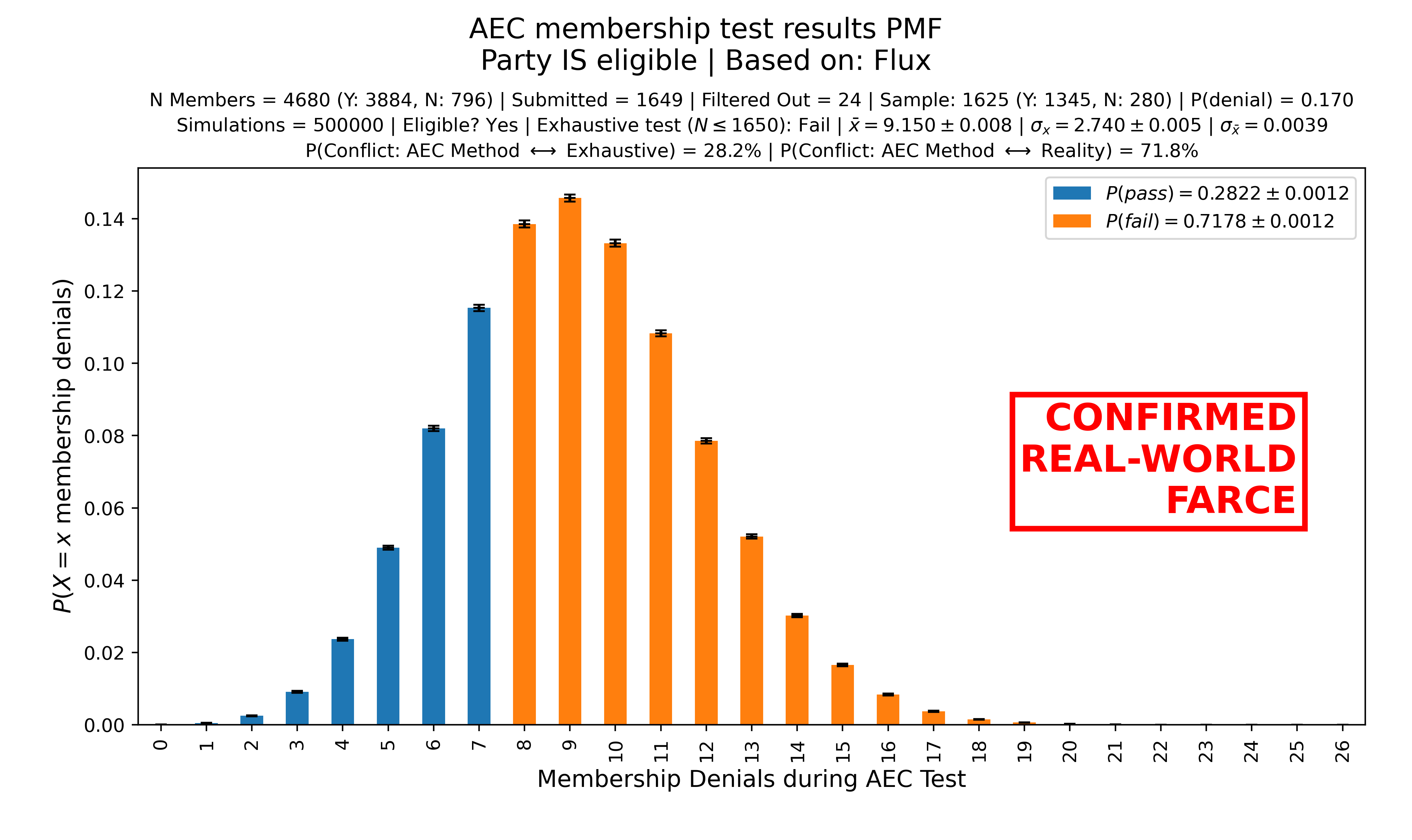

In the case of Flux’s recent membership audit, the simulation shows that – on the assumption that Flux is an eligible party, and that 17% of members provided will respond “No” – that there is a 71.7% chance of the AEC reaching a false negative result. In such a case, based on the AEC’s data, statisticians should expect that Flux has over 3,800 members that would either respond “Yes” or not respond. See Fig 5.1.

What if we repeat the exercise? How many membership tests would be required to reach a positive result 90% of the time (i.e., 10% of the time Flux fails every test)?

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.283) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 5 |

| 90% | 7 |

| 95% | 10 |

| 99% | 14 |

So, 7 complete tests (of 1650 members randomly sampled from Flux’s list of 4680) would be required to reach 1 successful test, 90% of the time.

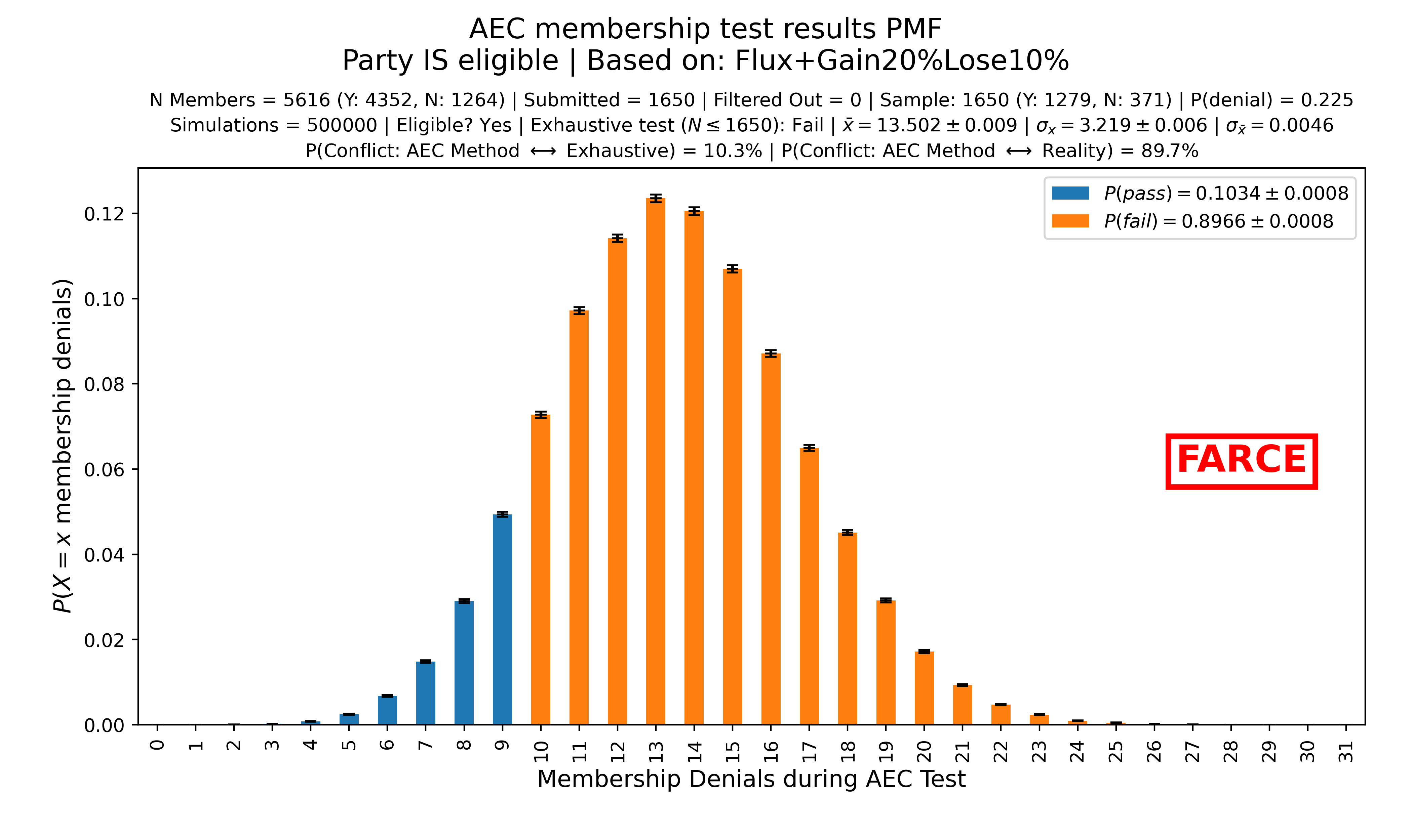

What happens if Flux gains more members?

Moreover, say that Flux is gaining members faster than it is losing them. (‘Losing’ members means that they will now answer “No” but do not revoke their membership.) It turns out that this can make the AEC’s methodology less likely to succeed. Go figure: a party increases it’s membership and the AEC test get’s less accurate! See Fig 5.2, Example 5.2.1, Example 5.2.2 (Filtered=0), Example 5.2.3 (Filtered=24).

The system is rigged. It’s a farce.

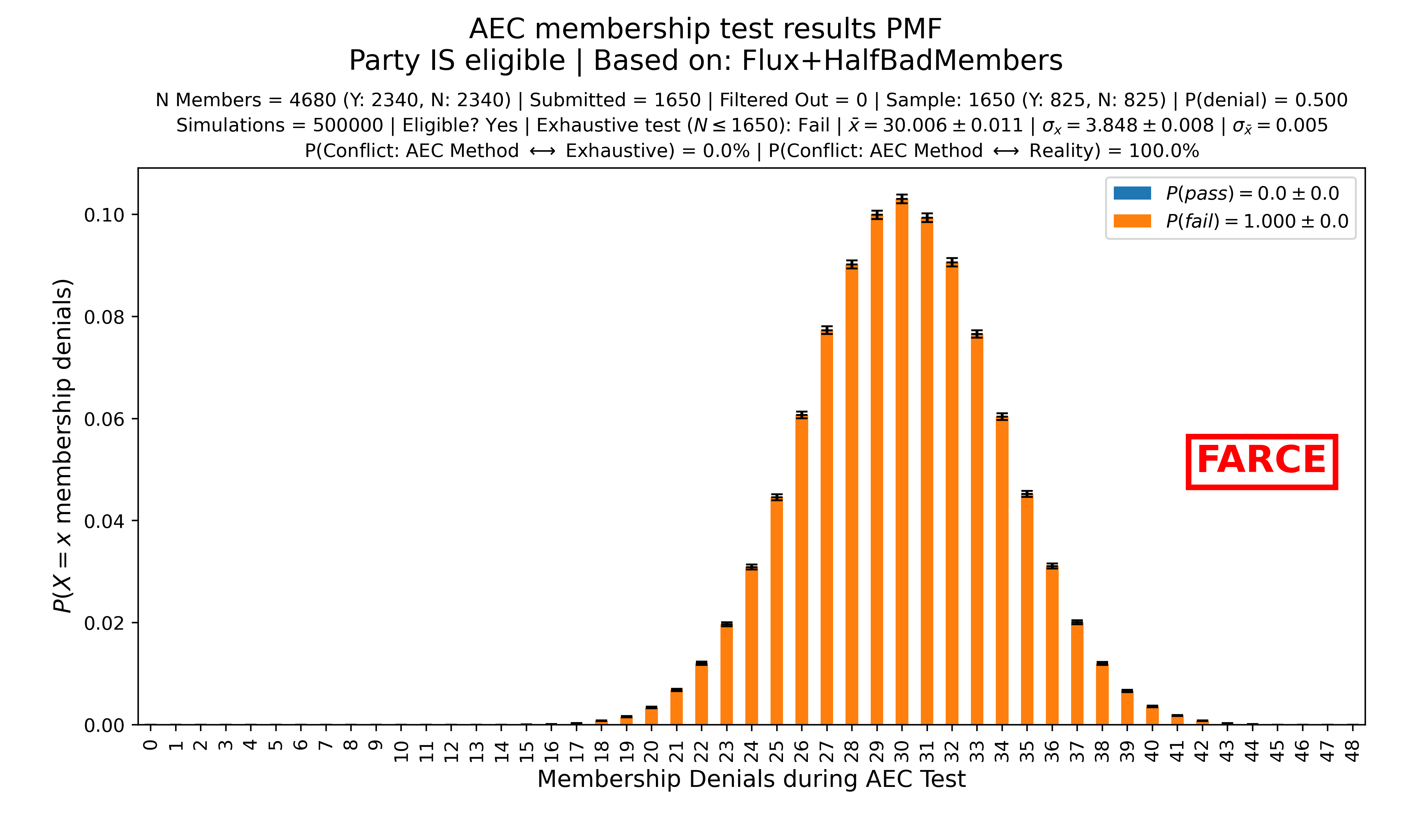

Finally, there are cases where the AEC’s method fails even more spectacularly.

Say 50% of Flux’s 4680 members submitted (as part of our objection to the AEC’s consideration of involuntary deregistration) respond “No” – the AEC’s method fails 100% of the time in this case, even though Flux would exceed the legislative requirement by 1.56x. See Fig 5.3, and related: Example 5.3.1.

Update: additionally, see 8. Flux’s Second Membership Test (March 2022).

Reading These Graphs

Note: some mathematical notation below won’t render correctly if you view this on GitHub. To assist with this, an English translation is provided in quotes beforehand. Note that the problem entries (x bar, sigma sub x, etc) are presented below in the same order as the subtitles of the figures.

- N Members: The number of members that the party is capable of submitting, i.e., they are validated to the best of the party’s ability.

- Submitted: The number of members that the party submits to the AEC.

- Filtered Out: The number of members removed without replacement by the AEC – parties cannot preemptively remove these members as the AEC uses information that is unavailable to parties.

- Sample: The number of members after AEC filtering.

- P(denial): The probability that a member will deny membership when contacted.

- (Y: …, N: …): The number of members that, when contacted by the AEC, will respectively respond: “yes”, and “no”. Note: if a member does not respond to a request for contact, the AEC selects a new member to contact from the sample.

- Simulations: The number of times the AEC test was simulated while generating the distribution.

- Eligible?: whether the party is eligible under the Electoral Act.

- Exhaustive test: would the party pass a membership test if every member in the sample group were contacted? Note: this is limited by AEC policy to 1650 (or 550 prior to Sept 2021).

- “x bar” (): The mean of the distribution, i.e., the average number of denials.

- “sigma sub x” (): Standard deviation of the distribution.

- “sigma sub x bar” (): Standard error of the distribution.

- P(Conflict: AEC Method ↔ Exhaustive): The probability that the AEC’s method conflicts with the results of an exhaustive test.

- P(Conflict: AEC Method ↔ Reality): The probability AEC’s method fails (i.e., produces a false positive or false negative).

- ±: This indicates the 95% confidence interval. That is: the 95% confidence interval for a±b has a lower bound of a-b and an upper bound of a+b.

- Data in each chart has error bars in black.

Analysis of Flux’s actual membership test

Fig 5.1: Even though an assumption of this simulation is that Flux is an eligible political party, the AEC's method fails 71.7% of the time. This is the real-world analysis of Flux's membership test.

Note: Flux submitted 1649 members due to an off-by-one error (the spreadsheet had 1650 rows, including a row for the headings).

Predictive analysis if Flux’s membership increases by 20% but members that will deny membership increases by 10%

Fig 5.2: This distribution shows that the AEC's validation method becomes less reliable as a party *gains* members.

Improvement makes life harder! Strength is weakness!

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.104) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 15 |

| 90% | 21 |

| 95% | 28 |

| 99% | 42 |

Predictive analysis with a 50% denial rate

Fig 5.3: If we assume that Flux provides 4680 members but only 50% of them will respond "Yes" or not respond -- indicating 2340 valid members and indicating that Flux is an eligible party -- the AEC's method fails 100% of the time.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p<0.0005) |

|---|---|

| 80% | at least 3,219 |

| 90% | at least 4,605 |

| 95% | at least 5,990 |

| 99% | at least 9,209 |

6. Suspected Farces

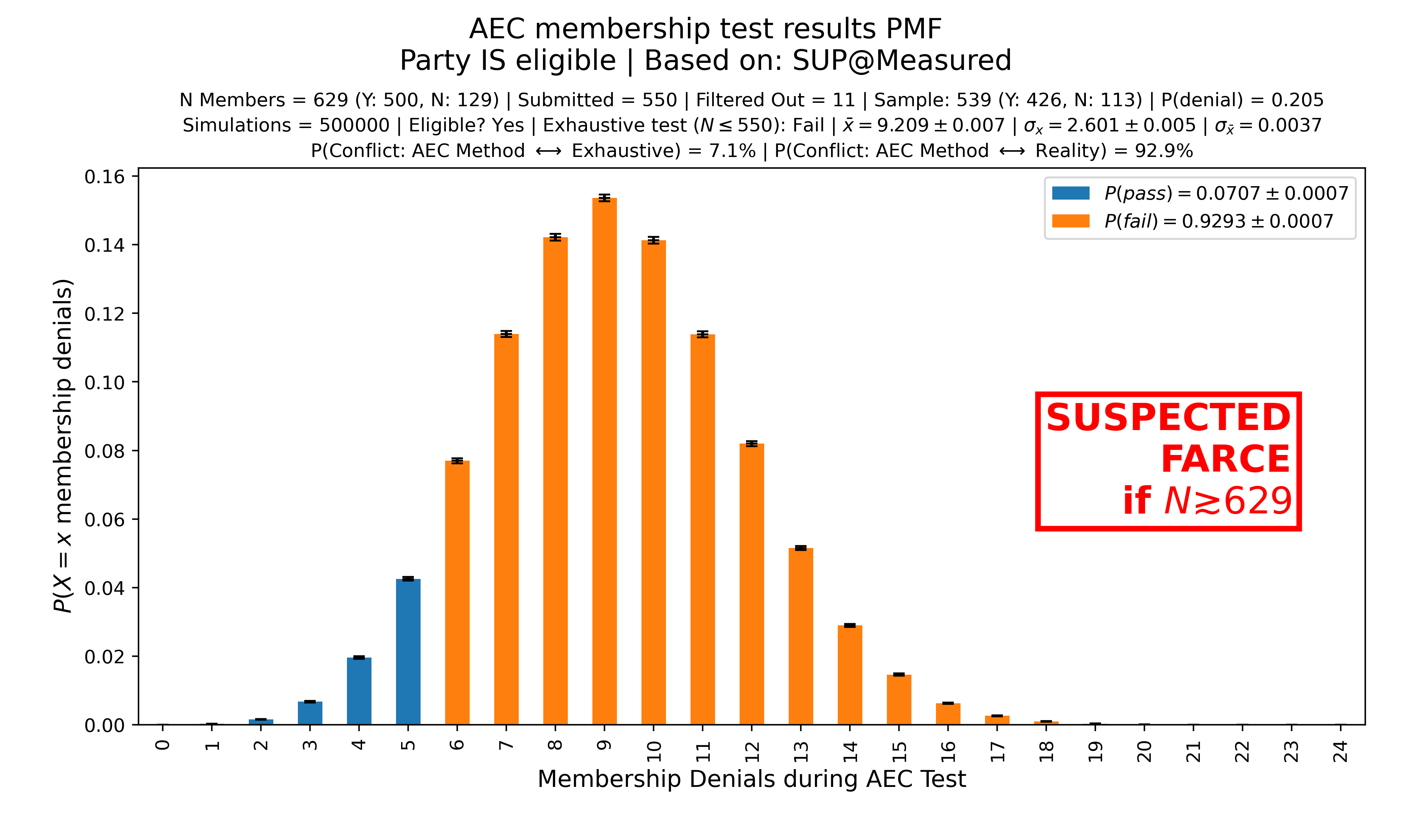

Detecting previous farces is difficult because the AEC does not publish the results of membership tests and, to my knowledge, does not record or ask for the number of members a party could offer in support of their validity. Instead, we only know the number of members that were submitted, which is always ≤ 1650 (or the limit in effect at the time), and we only know this when the AEC has published a statement of reasons which is only done when there is a request for review. If a party just gives up, or otherwise misses the deadline, then we don’t hear about it and thus cannot evaluate whether a farce occurred.

Note: these cases occurred prior to the September 2021 increase in required members. Therefore they are judged against the previous requirements – the test method was practically the same, the only difference being that it was calibrated for membership lists of 500-550 instead of 1500-1650.

Since parties sometimes max out the number of members they may provide, the only reasonable conclusion is that they have more members they could provide if a more responsible method were used.

Therefore, parties are assumed to have just enough excess capacity in additional members to be eligible, and that those extra members could have been provided.

Excess Capacity Explanation

Excess capacity here refers to additional members that, if not for the AEC’s limit, a party could provide – expressed as a percentage of the limit. If a party requires 10% excess capacity, and the limit of a membership list is 1650, then that party must be capable of providing a list of 1815 members that a list of 1650 members is randomly sampled from.

For comparison: in Flux’s case, we had 3030 additional members (excess capacity of 184%) – excluding those that we could not validate. The AEC is sometimes able to validate members that we cannot, and we have at least 4285 additional members that we could contact with a request for them to update their details.

What about cases where the member list submitted had a large number of duplicates? It is not safe to assume the absence of a farce in these cases: maintaining membership lists is difficult. In my case, I wrote thousands of lines of custom code to assist Flux in managing our member list – and the proportion of our list that is automatically matched against the electoral roll is proof of this. But, even with multiple checks for duplicates (matching phone numbers, emails, first and last names, etc), still we would occasionally get duplicates. These stragglers were usually found through a manual process before submission. At some point it just isn’t worth worrying about. However, due to the ambiguity of these cases, this document will exclude them from “suspected” farces.

The Suspected Farces

Since, in the following cases, the excess capacity of the party undergoing testing was not known, these are only suspected farces.

- (Fig 6.1) 30 June 2021 – deregistration of Child Protection Party under s 137(6) (mirror) – excess capacity of 13.4% required

- (Fig 6.2) 9 March 2021 – deregistration of Seniors United Party under s 137(6) (mirror) – excess capacity of 14.4% required

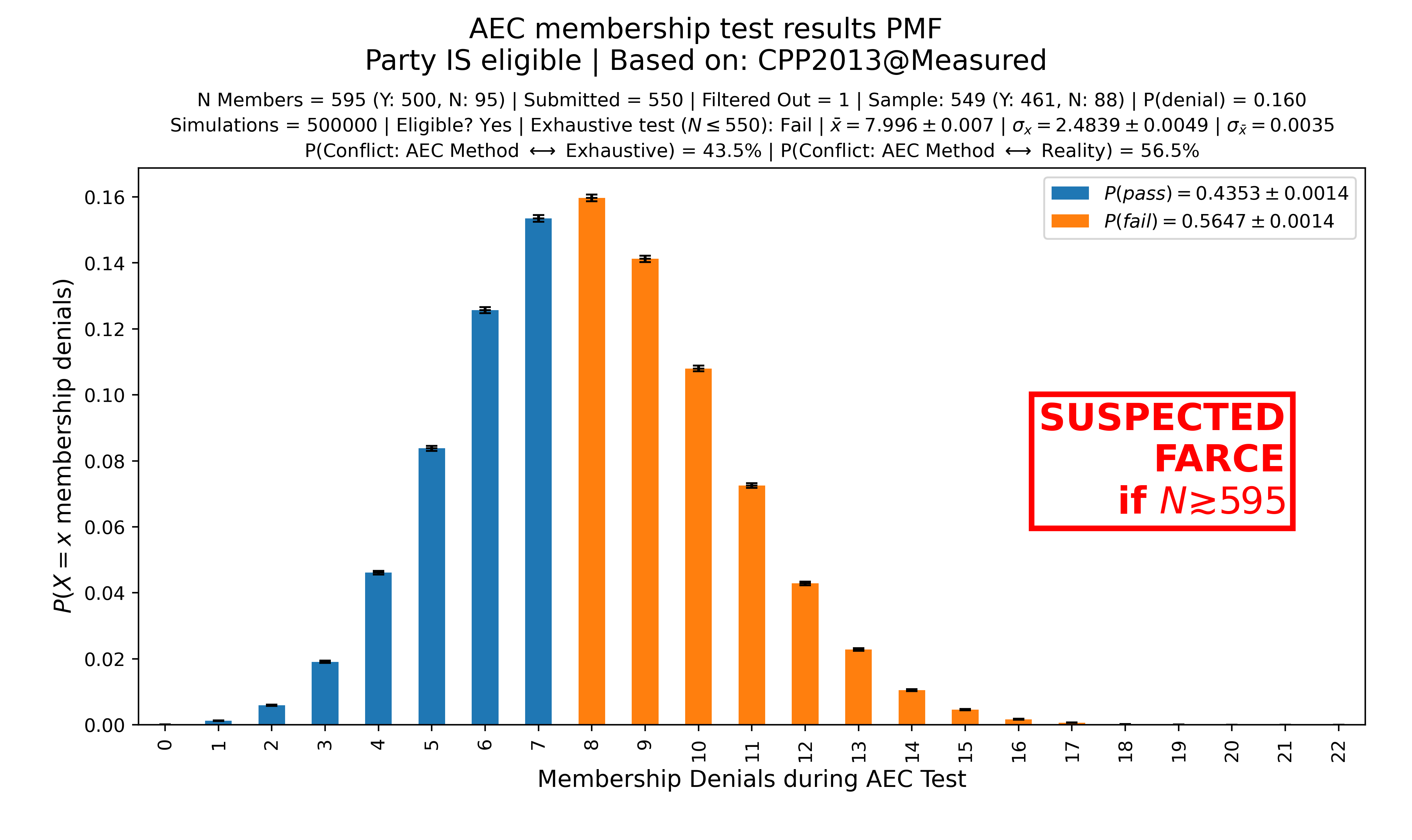

- (Fig 6.3) 7 November 2013 – refusal to register of Cheaper Petrol Party (mirror) – excess capacity of 8.2% required

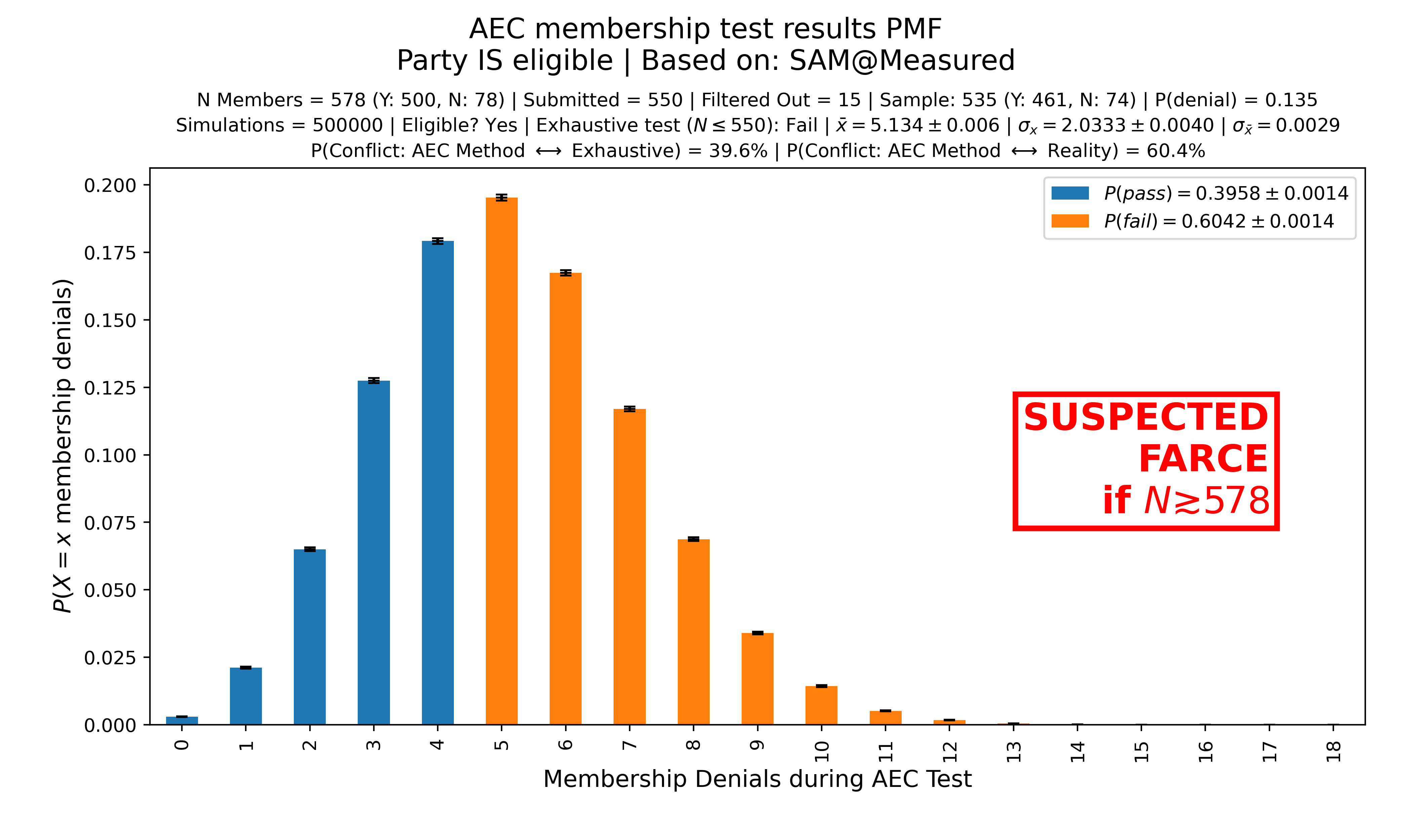

- (Fig 6.4) 12 November 2010 – refusal to register of Seniors Action Movement (mirror) – excess capacity of 5.1% required

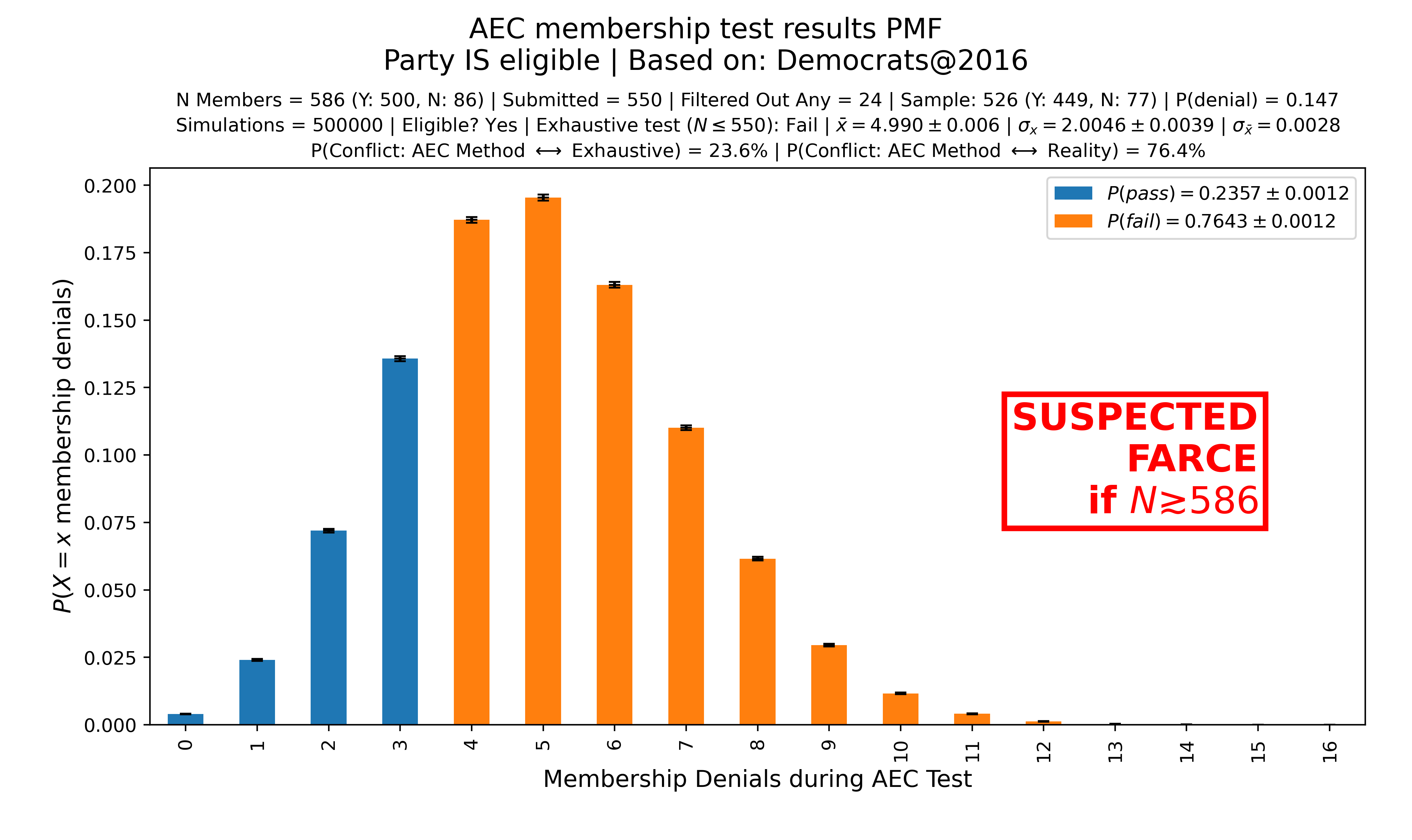

- (Fig 6.5) 1 March 2016 – deregistration of the Australian Democrats (mirror) – excess capacity of 6.5% required

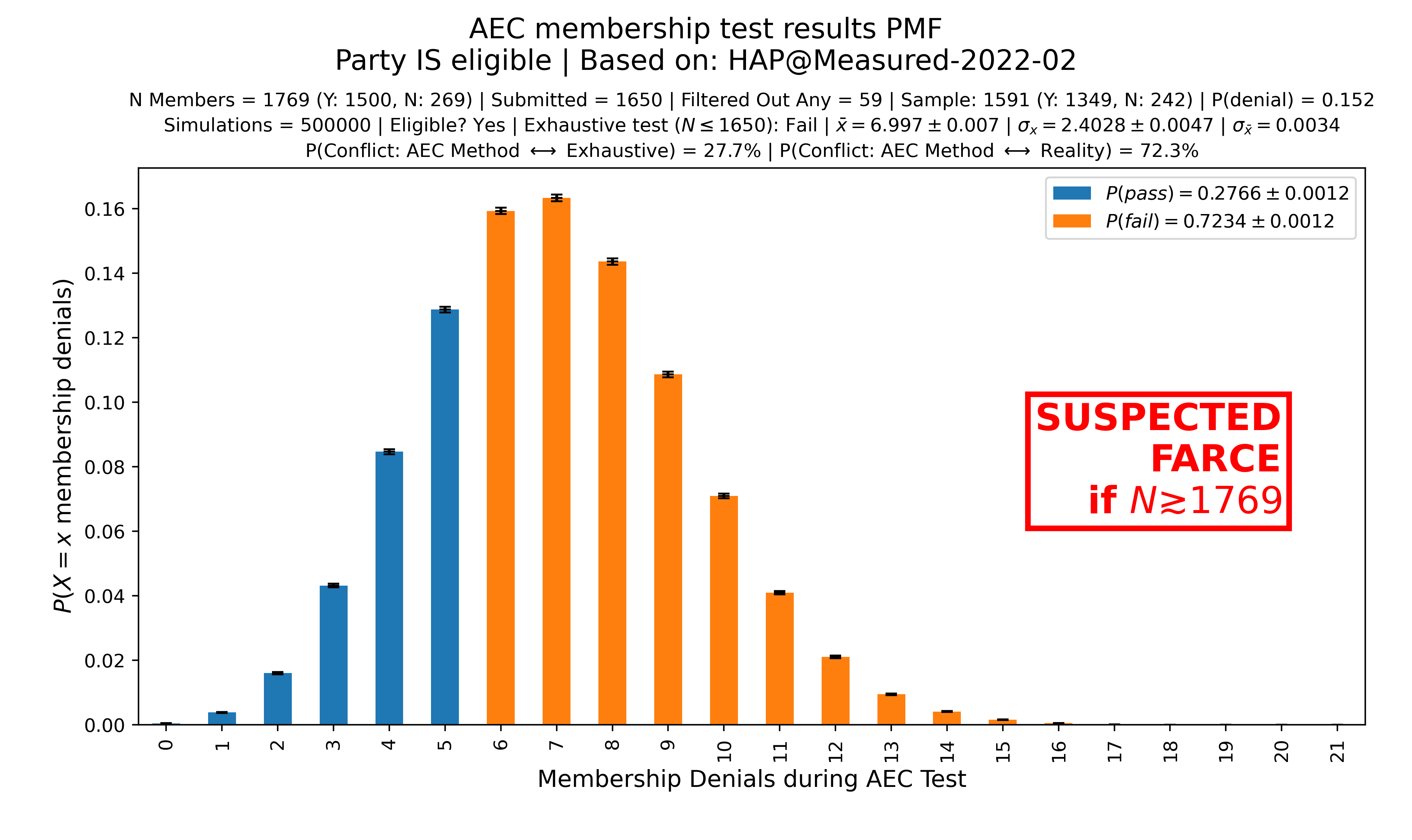

- (Fig 6.6) 5 April 2022 – deregistration of Health Australia Party (mirror) – excess capacity of 7.2% required (Added in update on 2022-04-14)

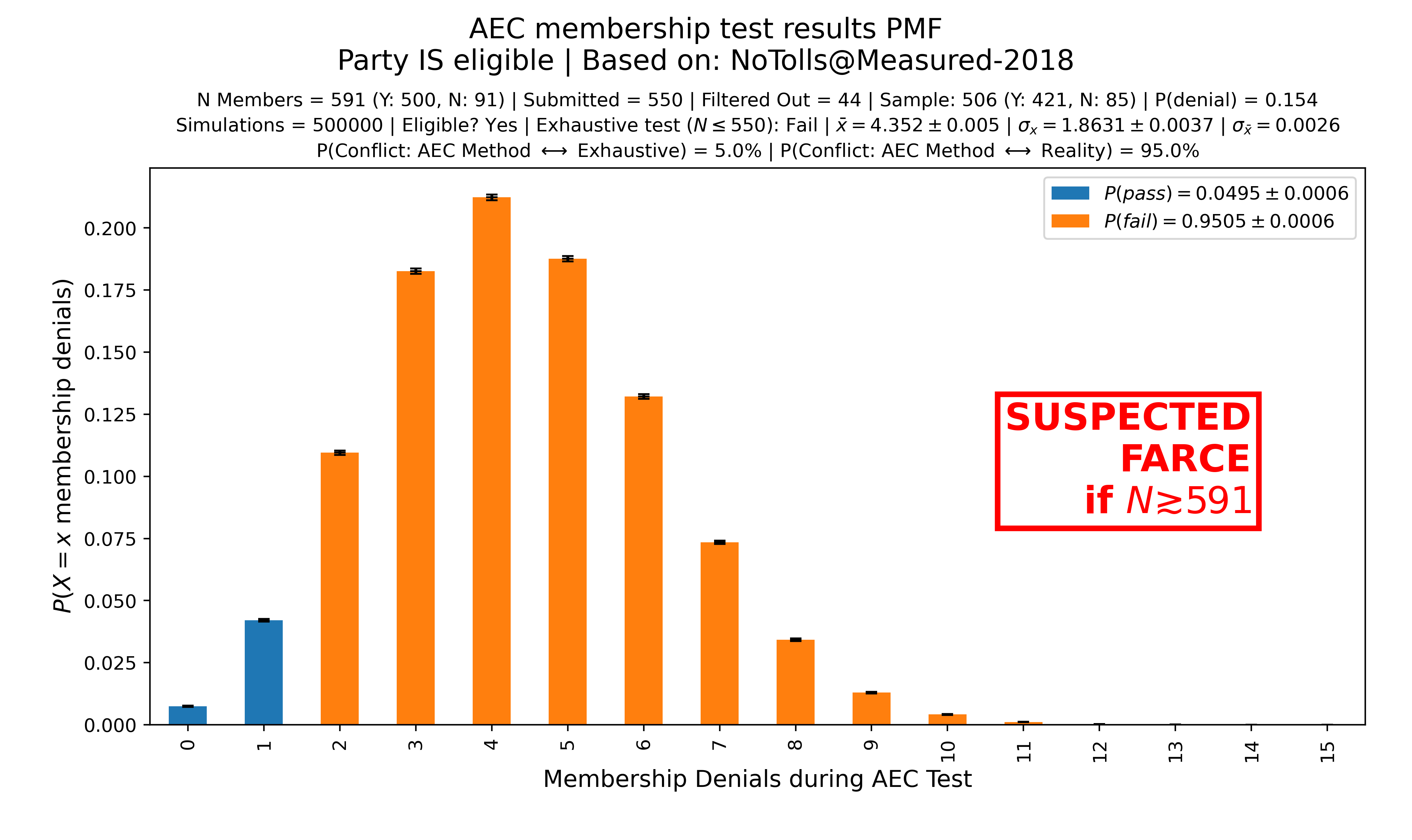

- (Fig 6.7) 30th August 2018 – affirmation of decision to deregister Consumer Rights & No-Tolls (mirror) – excess capacity of 7.5% required (Added: 2022-04-16)

Note, the @Measured in the titles of the following graphs indicates that the failure rate is calculated directly from AEC reports of the ratio of membership denials to membership contacts.

Fig 6.1: The deregistration of Child Protection Party on 30 June 2021 is suspected to have been a farce.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.176) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 9 |

| 90% | 12 |

| 95% | 16 |

| 99% | 24 |

Fig 6.2: The deregistration of SUP on 30 June 2021 is suspected to have been a farce.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.071) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 22 |

| 90% | 32 |

| 95% | 41 |

| 99% | 63 |

Fig 6.3: The refusal to register Cheaper Petrol Party on 7 November 2013 is suspected to have been a farce.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.435) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 3 |

| 90% | 5 |

| 95% | 6 |

| 99% | 9 |

Fig 6.4: The refusal to register SAM on 12 November 2010 is suspected to have been a farce.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.410) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 4 |

| 90% | 5 |

| 95% | 6 |

| 99% | 9 |

Fig 6.5: The affirmation of the decision to deregister of the Australian Democrats on 1 March 2016 is suspected to have been a farce. Note: this uses the AEC measured P(denial), as with graphs including @Measured.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.237) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 6 |

| 90% | 9 |

| 95% | 12 |

| 99% | 18 |

Fig 6.6: The deregistration of Health Australia Party on 5th April 2022 is suspected to have been a farce. Both of HAP's membership tests were farcical. See also: their November 2021 test.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.277) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 5 |

| 90% | 8 |

| 95% | 10 |

| 99% | 15 |

Fig 6.7: The affirmation of decision to deregister Consumer Rights & No-Tolls on 30th August 2018 is suspected to have been a farce.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.050) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 32 |

| 90% | 46 |

| 95% | 60 |

| 99% | 91 |

Possible Farces

These are cases where the available information regarding the membership test is incomplete, so some assumptions have had to be made. Based on AEC measurements, if the party had some minimum number of members (such that it had at least 500 non-denying members), then these cases are farces.

- 2017-08-09 Affirmation of refusal to register the Australian Affordable Housing Party – Figure

- 2016-05-04 Set aside of decision to deregister Australian First Party – Figure Note: this is a farcical situation because, although the party was successful, the accuracy was only 48.8%. In essence, it was a 50/50 coin-flip.

- 2017-08-09 Refusal to register The Communists – Figure

- 2018-08-30 Refusal to register Voter Rights Party – Figure

- 2016-08-24 Affirmation of deregistration of the Republican Party of Australia – Figure

7. Flux’s 2021 Membership Test Assuming a Threshold (9.09%) Denial Rate (including worst-case)

Flux is a party that has – with regards to membership lists – excess capacity; if filtered members could be replaced, we could provide them. Note that filtered members are never replaced in the AEC’s method.

Given this, combined with the artificial limit on sample size, what are the true accuracy values for the AEC’s test?

As it turns out, it depends on the quality of Flux’s membership list. We have a high-quality list – thanks to a lot of management code written to help with that – but many parties do not have the skills or resources to do that.

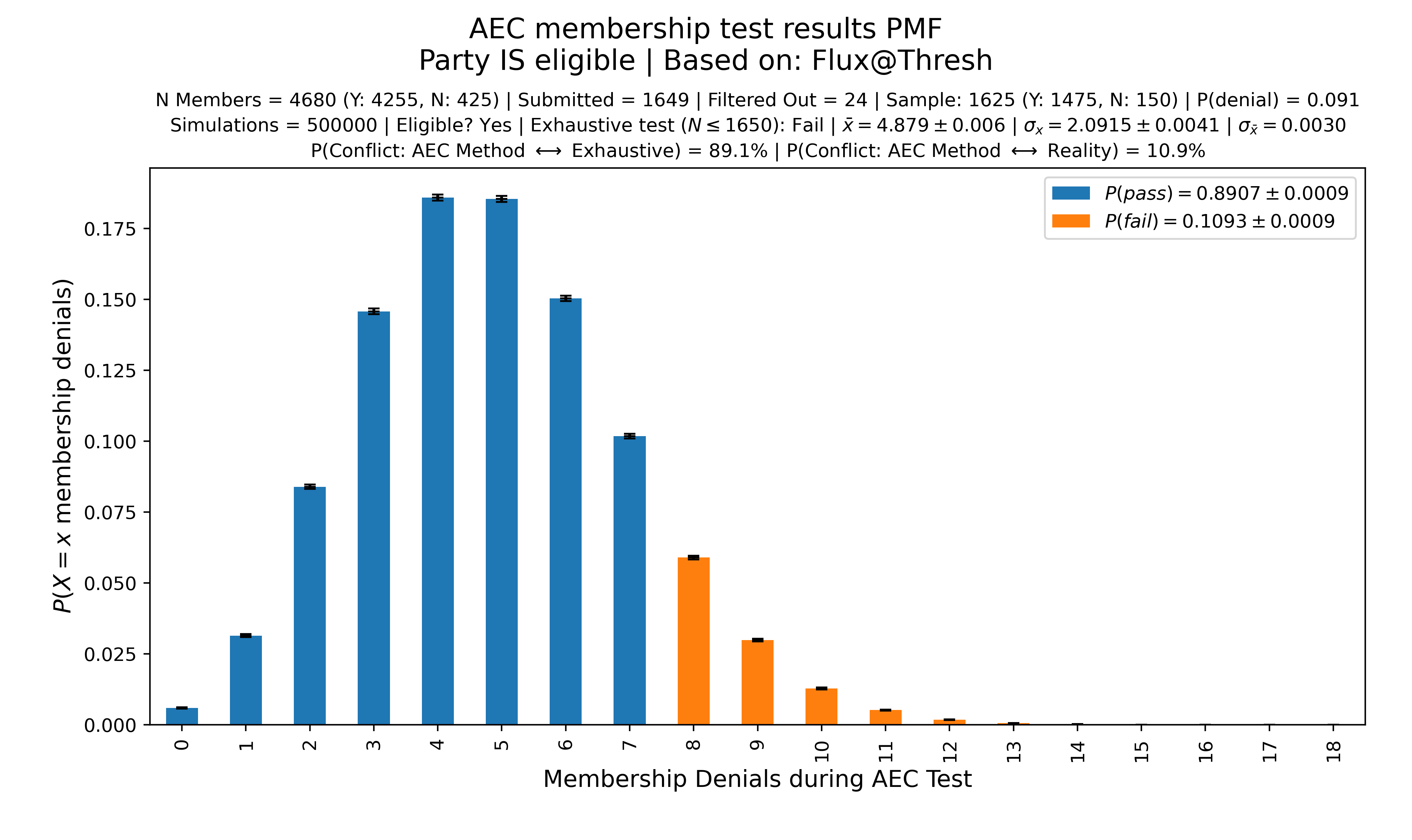

Fig 7.1 shows that, for Flux’s recent membership test, the true accuracy of the AEC’s method – assuming that Flux’s members have P(denial) = 0.0909 – was 89.0%; which is lower than the 90% accuracy that’s been advertised in the past. That means that the results of the AEC’s test would incorrectly find Flux ineligible 11% of the time.

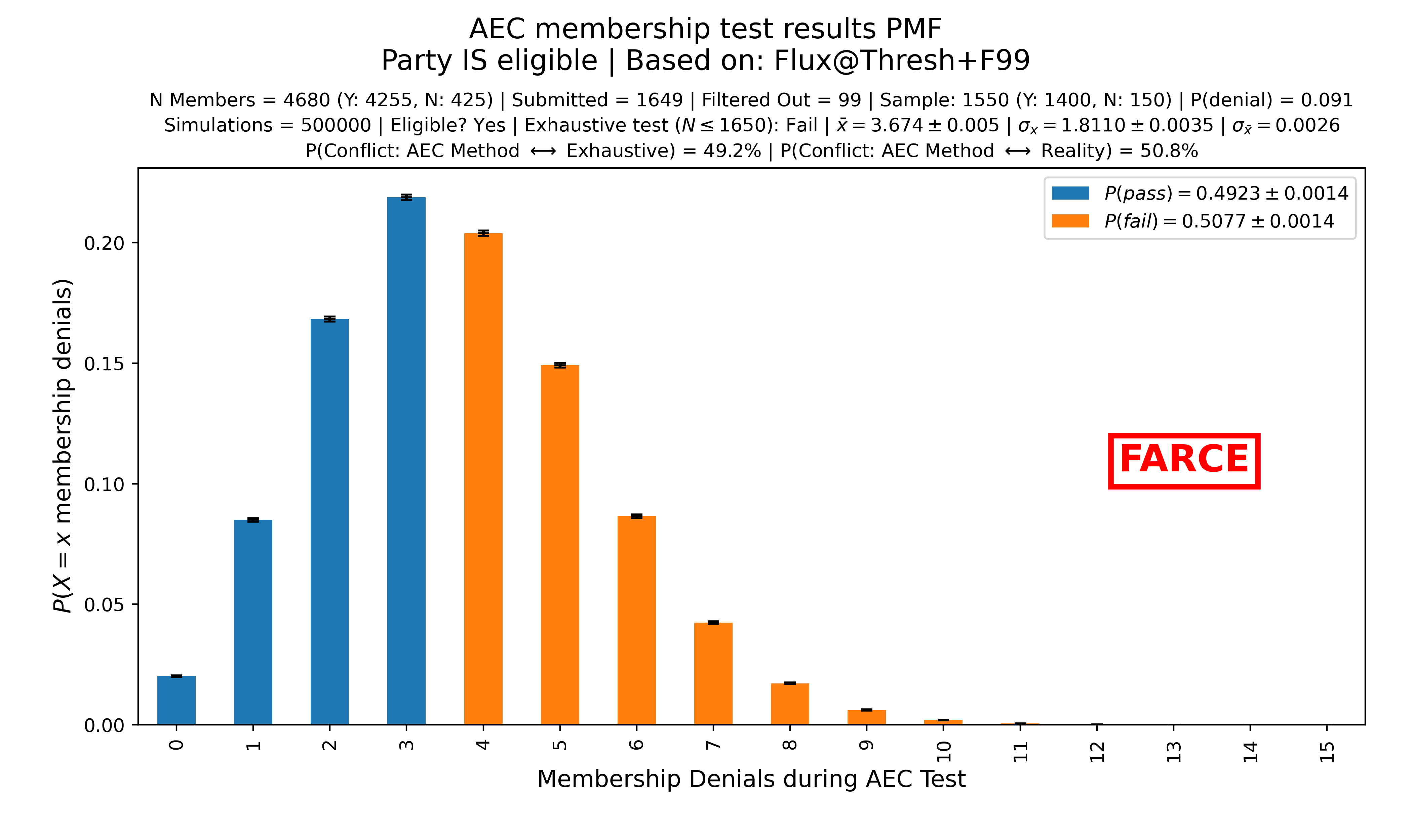

Additionally, Fig 7.2 and 7.3 show that, as the number of members filtered out increases, accuracy drops – a lot.

@Thresh in these titles indicates a 9.09% denial rate (which is not what was measured during Flux’s recent membership test). 9.09% = 150 / 1650.

+F__ indicates that the number in place of __ is the number of members that were filtered out (e.g., duplicates, deceased members, etc).

Fig 7.1: Assuming that 91.9% of the members (randomly sampled from the full list) on Flux's 2021 membership test will not deny membership when contacted (1500/1650): 500,000 simulations of Flux's membership test show that it has an accuracy of 89.0% (i.e., false negative rate of 11.0%), which is less than the AEC's previously advertised 90% accuracy.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.890) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 1 |

| 90% | 2 |

| 95% | 2 |

| 99% | 3 |

Fig 7.2: Assuming that 91.9% of the members on Flux's 2021 membership test members will not deny membership when contacted (1500/1650), and that 99 members were filtered out instead of 24: 500,000 simulations show that it is 49.2% accurate, which would constitute a farce. With a membership list of this quality, 4 membership tests would be required for a 90% chance of 1 success.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.492) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 3 |

| 90% | 4 |

| 95% | 5 |

| 99% | 7 |

Fig 7.3: Assuming that 91.9% of the members on Flux's 2021 membership test members will not deny membership when contacted (1500/1650), and that a worst-case 149 members were filtered out instead of 24: 500,000 simulations show that it is accurate just 15.1% of the time, which would constitute a farce. With a membership list of this quality, 15 membership tests would be required for a 90% chance of 1 success.

| Chance of 1 Success | Tests Required (p=0.151) |

|---|---|

| 80% | 10 |

| 90% | 15 |

| 95% | 19 |

| 99% | 29 |

8. Flux’s Second Membership Test (March 2022)

After Flux’s response in February 2022, the AEC decided of its own accord to conduct another membership test. Flux did not request this. In fact, it makes no sense for Flux to request this because we were primarily concerned with the inability of the test to function as intended. The AEC ignored our criticisms. It appears that the AEC does not care about reason, or logic, or statistical arguments.

As though to emphasize the fact that the AEC’s method is a joke, the AEC’s statement of reasons [mirror], authored by one Ms Reid, says:

22. The membership list submitted by the Party on 13 February 2022 contained 4,680 names of individuals that the Party considers to be current members (referred to as ‘members’ below). As a delegate of the Electoral Commission, I instructed that the top 1,650 names be tested to conform with the AEC’s membership testing parameters. […]

The membership list that we submitted was sorted alphabetically by first name. “Gloria” was the first member to miss out on the chance to be contacted. Every member whose first name came later than hers, alphabetically, was excluded.

The Statement of “Reasons”

Let me grace you with the AEC’s wisdom.

First, consider that Flux did not ask for another membership test, and argued that the method was invalid; the list of 4680 members was not provided for the purpose of a membership test, it was provided as evidence that the AEC’s method was in conflict with reality.

The “supporting statement” comprises:

25. I have considered the statement lodged by the Party on 13 February 2022, setting out reasons why the Party should not be deregistered.

[Omitted: quotes of Flux’s February 2022 response]

26. I reject the reasons outlined by the Party in its statement provided on 13 February 2022 for the following reasons.

27. The Party failed membership testing for exceeding the maximum number of permitted denials according to the ABS methodology used by the AEC. It did not fail membership testing due to having an insufficient number of members being identified on the electoral roll.

28. The Electoral Act defines an elector as someone that is on the Commonwealth Electoral Roll. Section 123 of the Electoral Act prescribes that an eligible political party, not being a Parliamentary party, has ‘at least 1,500 members’. The requirement is not to be solely ‘an elector’ but to be a member of the party.

29. The Party challenges the validity of the AEC’s membership testing process. This process has been developed by the AEC to support the delegate’s consideration of whether a party has sufficient members. It is based on sampling methodology designed in consultation with the ABS and provides a valid methodology to satisfy a delegate of a party’s membership. The Electoral Commission has previously concluded that the methodology ‘was appropriate for membership testing, including because it was rational, fair and practical in all the circumstances.’1

30. I consider that the membership testing results outlined above provide a more robust method for ascertaining whether a party has satisfied the requirements of the Electoral Act than a statement provided by the party.

31. In summary, I remain satisfied that the Party does not have at least 1,500 members based on the outcomes from membership testing both membership lists of 7 December 2021 and 13 February 2022.

32. Accordingly, in my capacity as a delegate of the Electoral Commission, I have deregistered VOTEFLUX.ORG | Upgrade Democracy! under s 137(6) of the Electoral Act and the particulars of the Party have been cancelled from the Register under s 138 of the Electoral Act.

Here is a brief analysis of the insanity of the above:

- Point 25 is dishonest – Flux’s arguments were ignored (update: seemingly confirmed by LEX3132 (docs schedule, files)). Moreover, the exact thing that we criticized was the first thing that Ms Reid did.

- Point 27 is largely irrelevant, it doesn’t respond to anything that we said. It also contradicts point 29, which starts: “The Party challenges the validity of the AEC’s membership testing process.” If Ms Reid knows this, why did she make point 27? That the AEC method failed in spite of Flux having sufficient members is the reason for Flux’s objection in the first place. What Ms Reid omits, of course, is that it is AEC policy (and AEC policy alone) that prevents a party from submitting additional members.

- Point 28 actually supports Flux’s case: we should be able to submit more members than AEC policy currently allows. Ms Reid implies that this supports point 27, which in turn implies that the AEC method is remotely accurate (this has been proven false by the earlier sections of this paper). The purpose of point 28 is to dishonestly imply that the AEC’s decision (and policy) are supported by the Electoral Act (EA) – but this isn’t the case. If the AEC wanted to use the EA to support their case, they should cite the parts that say the commissioner can do what they damn well please, without repercussion.

- Point 29 is an argument from authority and dishonestly evades the arguments that Flux made. This is an outline/summary of what point 29 says:

- The party says the method is bad.

- But the AEC developed this policy.

- And the AEC consulted with the ABS.

- It is valid.

- Here is a time that we said it was valid.

Of course, the AEC has never published anything to support this claim, and neither has the ABS. It’s a party’s word against the AEC’s, but the AEC is also the adjudicator. Hmm.

- The document cited to support point 29 is for a different testing procedure – did Ms Reid’s expert statistical knowledge inform her that the methods were comparable and that nothing substantial had changed? We may never know. At least, the AEC won’t volunteer such information. Why should they? After all, it doesn’t really matter whether the commission responsible for maintaining our democracy is rational, reasonable, or even knows early high-school maths, does it? If it did matter, surely we would have noticed by now.

- The document cited to support point 29 says:

8. […] The Commission noted that this methodology was the same as the sampling methodology recommended by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (‘ABS’). The Commission concluded that the methodology was appropriate for the purpose of membership testing, including because it was rational, fair and practical in all the circumstances.”

So, the Commission, to argue for their conclusion, cites another time they claimed, also without reason, a similar conclusion for a different method. Well, we have seen both claims proven false, here, haven’t we?

This sort of evasion is to be expected. A different reason was given by the AEC in 2018 – that example is cited in 9. Feedback Loops Between AEC Policy and Party Behavior.

-

30. I consider that the membership testing results outlined above provide a more robust method […] than a statement provided by the party.

Yes, indeed. That is her educated opinion as a statistician, I’m sure.

As it turns out, there is nothing that a party could say that would change the AEC’s mind. That is dangerous. If the AEC is wrong, how will they know? They have no method. No error correction. Watch and see.

What should we have expected from this second membership test?

Fig 8.1: Despite being eligible under the Electoral Act, Flux could never have passed the AEC's test. In this case, the AEC's method has a failure rate > 99.996%. In the AEC's words, this test is "rational, fair and practical in all the circumstances". What a joke.

Rigged. There isn’t much more to say.

9. Feedback Loops Between AEC Policy and Party Behavior

To my knowledge, parties typically don’t try to build membership to many thousands of members. That’s because it’s expensive, time consuming, and difficult to manage. Most importantly – there’s no point when it comes to registration.

The fact that the AEC has imposed this flawed method for years means that non-parliamentary parties’ common practices are based around meeting the AEC’s policies. When the limit was 550 (and 500 members required), there literally was no point building beyond that because it would not help you in registering or maintaining registration – it was largely wasted effort.

Additionally, the AEC’s policies have entrenched these common practices which enabled the political elite to change the legislative requirements suddenly and dramatically – effectively eliminating the competition. The AEC is complicit.

If the previous status quo was 550 members due to the AEC promulgating a culture of not going beyond this, and then parliament decides to radically change the limit (there is no reason they could not have done this gradually over, say, 10 years with a small bump each year), at what point do we acknowledge that something is rotten?

The AEC is on record about why it imposes a limit on membership lists used for verification:

26. In respect of the assertion in the application for review that the AEC failed to test the lists provided by the Party on 12 June 2017 (which contained 650 members) and on 20 August 2017 (which contained 739 members), the Commission notes that the ‘Party Registration Guide’ requests that parties provide a list of between 500 to 550 members. This is considered to be to a party’s advantage, by minimizing the work required of the party in confirming the enrolment status and contact details of additional other members.

Source: https://www.aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/Registration_Decisions/2018/2018-commonwealth-of-australia-party-statement-of-reasons.pdf (mirror)

Note: this case cannot be analyzed as the AEC neglected to include any results of membership tests.

How about the AEC stop making decisions on behalf of parties? Especially when those decisions have been proven (by this document) to have systemically disadvantaged non-parliamentary parties, to have decreased the accuracy of the AEC membership test, to be based on falsehoods, and, ultimately, to be a reflection of a condescension and hubris that has no place running a democracy.

10. Conclusion

With the AEC’s existing policies, and on the assumption that Flux is a valid party, it is only reasonable to conclude that Flux will find it increasingly difficult to remain registered and pass registration tests, even if it grows in membership. This applies to all nonparliamentary parties. That is to say: the process has a predetermined outcome, and is an empty act done for show. It is rigged, and a farce.

With currently measured values (based on AEC results), it would take (on average) 7 repeated trials for Flux to have 1 successful membership test. So this is not a problem that can be solved by repeating the membership test.

At least 5 past cases have been identified with farcical properties – they are suspected farces – and at least 5 additional cases have incomplete information but may be farcical.

That is: in these cases the AEC’s test is less than 50% accurate, provided that those parties had additional members (which the party would have been prevented from submitting only due to AEC policy). All 5 suspected cases required less than 15% additional members – i.e., the membership test was a farce for all cases if N ≥ 630. Note that all 5 cases predate the September 2021 change to membership requirements; at the time the required number of members was 500.

It has thus been found that the AEC’s method is rigged and a farce, and that there is sufficient evidence to back this up.

Appendix: Definitions

rigged adjective

- Pre-arranged and fixed so that the winner or outcome is decided in advance.

- The word rigged is used to describe situations where unfair advantages are given to one side of a conflict.

Note: Urban Dictionary is included here as Cambridge and Merriam-Webster didn’t seem to have specific definitions for the adjective.

rig verb

(Note: rigging is the gerundive of rig)

- to arrange an event or amount in a dishonest way

- to dishonestly influence or change something in order to get the result that you want

- To manipulate something dishonestly for personal gain or discriminatory purposes.

farce noun

- a situation that is very badly organized or unfair

- a ridiculous situation or event, or something considered a waste of time

- A situation abounding with ludicrous incidents.

- A ridiculous or empty show.

- an empty or patently ridiculous act, proceeding, or situation

Appendix: AEC Membership Testing Tables

Note: the first column of these tables (“Members lodged”, “Eligible membership”) is the reduced membership list after filtering out e.g., duplicates, members supporting the registration of other parties, deceased members, etc.

It is “AEC Policy” that lists are no more than 1.1x the legislative limit (e.g., a maximum of 550 prior to September 2021, and 1650 after September 2021). That is: lists with more members than this are rejected.

September 2021 to February 2022

Source: Page 24 of https://web.archive.org/web/20220206003633/https://www.aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/guide/files/party-registration-guide.pdf

| Members lodged | Random sample size | Maximum denials to pass |

|---|---|---|

| 1,500 | 18 | 0 |

| 1,506 | 27 | 1 |

| 1,523 | 33 | 2 |

| 1,543 | 38 | 3 |

| 1,562 | 42 | 4 |

| 1,582 | 46 | 5 |

| 1,599 | 50 | 6 |

| 1,616 | 53 | 7 |

| 1,633 | 57 | 8 |

| 1,647 | 60 | 9 |

| 1,650 | 60 | 9 |

Experimental Eval (No Published Accuracy Values)

| Members lodged; N_reduced |

Measured risk of accepting 1200; P(denial) = (N-1200)/N; N = N_reduced; |

Measured risk of rejecting 1500; P(denial) = (N-1500)/N; N = N_reduced; f = 0 (no members filtered); |

Measured risk of rejecting ≥ 1500; (Threshold case); P(denial) = 150/1650 = 9.09%; N = 3300; f = 1650 - N_reduced; |

Measured risk of rejecting ≥ 1500; P(denial) = 20%; N = 3300; f = 1650 - N_reduced; |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1,500 | 1.8% fig | 0.0% fig | 82.2% fig | 98.2% fig |

| 1,506 | 1.6% fig | 0.5% fig | 72.0% fig | 98.2% fig |

| 1,523 | 1.7% fig | 1.2% fig | 58.9% fig | 97.3% fig |

| 1,543 | 1.8% fig | 1.9% fig | 45.9% fig | 96.2% fig |

| 1,562 | 1.9% fig | 2.3% fig | 33.3% fig | 94.4% fig |

| 1,582 | 1.9% fig | 2.8% fig | 23.6% fig | 92.2% fig |

| 1,599 | 1.8% fig | 3.1% fig | 16.4% fig | 89.9% fig |

| 1,616 | 2.0% fig | 3.2% fig | 10.3% fig | 85.9% fig |

| 1,633 | 1.7% fig | 3.7% fig | 6.9% fig | 83.3% fig |

| 1,647 | 1.8% fig | 3.6% fig | 4.1% fig | 78.8% fig |

| 1,650 | 1.7% fig | 4.0% fig | 4.2% fig | 78.9% fig |

Circa 2017 to September 2021

Sources:

- Page 26 of https://web.archive.org/web/20210409193623/https://aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/guide/files/party-registration-guide.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20200320074933/https://www.aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/files/party-registration-guide.pdf

| Members lodged | Random Sample | Max Denials to Pass |

|---|---|---|

| 500 | 18 | 0 |

| 503 | 26 | 1 |

| 511 | 32 | 2 |

| 519 | 37 | 3 |

| 526 | 41 | 4 |

| 534 | 44 | 5 |

| 541 | 47 | 6 |

| 548 | 50 | 7 |

| 550 | 50 | 7 |

Circa 2012 to 2016

Sources:

- Page 33 of https://web.archive.org/web/20160314113418/http://aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/files/party-registration-guide.pdf

- Page 32 of https://web.archive.org/web/20140212032435/http://www.aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/Party_Registration/files/party-registration-guide.pdf (Note: this source includes risk columns)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130208013723/http://aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/party_registration/guide/forms.htm#table (Note: this source includes risk columns)

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120425182026/http://www.aec.gov.au/Parties_and_Representatives/party_registration/guide/forms.htm (Note: this source includes risk columns)

| Members lodged | Random Sample | Max Denials to Pass | accepting only 400 – risk % | rejecting 500 – risk % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 18 | 0 | 1.80 | 0.00 |

| 503 | 26 | 1 | 1.99 | 1.05 |

| 512 | 30 | 2 | 2.64 | 3.26 |

| 521 | 34 | 3 | 2.86 | 4.68 |

| 529 | 38 | 3 | 2.85 | 5.52 |

| 537 | 42 | 5 | 2.60 | 6.65 |

| 543 | 46 | 6 | 2.43 | 6.86 |

| 548 | 50 | 7 | 2.27 | 6.78 |

| 550 | 50 | 7 | 2.07 | 8.05 |

Note: It seems likely that max denials to pass=3 for the members lodged=529 row is a typo – it should probably be 4, however, in all source documents it was 3.

In the 2016 RPA statement of reasons, a list of 530 lead to 38 contacts, and 4 or more denials was a fail (so max denials to pass=3). This typo has been enforced. (How many times? Only the AEC knows.)

According to the sampling methodology, as applied to a list of 530 names, if four or more people denied membership then the AEC could conclude that the party did not have 500 members.4

[Footnote 4:] According to the ABS, testing a sample of 38 from a list of 530 carried with it a 2.72% risk that the AEC could end up accepting a party that had only 400 members, and a 6.17% risk that the AEC could end up rejecting a party that had 500 members.

So there was a typo at some point, but the AEC actually used the typo to judge party membership. So a party with between 529 and 536 members during this period, with 4 denials, would have been wrongly denied even by the AEC’s own methodology. Also, the footnote values don’t match the previously advertised values in the table… is that just because it’s calculated for 530 instead of 529? Or did the AEC get an updated table in 2016 and those risk values changed? If they did change, why? (It’s not like the maths changed, right?)

The 2016 Australian Democrats statement of reasons confirms 34 contacts for a list of 526 with maximum 3 denials.

According to the sampling methodology, as applied to a list of 526 names, if four or more people denied membership then the AEC could conclude that the party did not have 500 members.3

[Footnote 3:] According to the ABS, testing a sample of 34 from a list of 526 carried with it a 2.30% risk that the AEC could end up accepting a party that had only 400 members, and a 8.53% risk that the AEC could end up rejecting a party that had 500 members.

Experimental Eval

Note: The row with members lodged=529 (corrected) corrects the erroneous max denials to pass from 3 to 4.

The AEC did not pick up on this error for at least 4 years (if they ever did).

| Members lodged; N_reduced |

Claimed: accepting only 400 – risk % | Measured risk of accepting 400; P(denial) = (N-400)/N; |

Claimed: rejecting 500 – risk % | Measured risk of rejecting 500; P(denial) = (N-500)/N; f = 0 (no members filtered); |

Measured risk of rejecting ≥ 500; (Threshold case); P(denial) = 50/550 = 9.09%; N = 1100; f = 550 - N_reduced; |

Measured risk of rejecting ≥ 500; P(denial) = 20%; N = 1100; f = 550 - N_reduced |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 1.80% | 1.7% fig | 0.00% | 0.0% fig | 82.3% fig | 98.2% fig |

| 503 | 1.99% | 1.8% fig | 1.05% | 0.8% fig | 70.1% fig | 97.8% fig |

| 512 | 2.64% | 2.3% fig | 3.26% | 2.8% fig | 52.3% fig | 95.8% fig |

| 521 | 2.86% | 2.5% fig | 4.68% | 4.1% fig | 37.4% fig | 93.3% fig |

| 529 | 2.85% | 0.7% fig | 5.52% | 14.6% fig | 45.9% fig | 96.3% fig |

| 529 (corrected) | 2.85% | 2.4% fig | 5.52% | 4.8% fig | 25.8% fig | 90.6% fig |

| 537 | 2.60% | 2.2% fig | 6.65% | 5.9% fig | 17.4% fig | 87.6% fig |

| 543 | 2.43% | 2.0% fig | 6.86% | 6.0% fig | 11.6% fig | 84.6% fig |

| 548 | 2.27% | 1.8% fig | 6.78% | 5.8% fig | 7.6% fig | 81.5% fig |

| 550 | 2.07% | 1.6% fig | 8.05% | 7.0% fig | 7.5% fig | 81.5% fig |

Circa 2011

The table below is an extract from a table based on a formula provided by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, giving approximately a 10% risk of refusing a party which has 500 members and a 2% risk of registering a party with only 400 members.

| Eligible membership | Size of random sample | Denials permitted | Confirmations required |

|---|---|---|---|

| 500 | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| 505 | 21 | 1 | 20 |

| 515 | 26 | 2 | 24 |

| 520 | 29 | 2 | 27 |

| 525 | 32 | 3 | 29 |

| 530 | 35 | 4 | 31 |

| 535 | 37 | 4 | 33 |

| 540 | 40 | 5 | 35 |

| 545 | 43 | 5 | 38 |

| 550 | 47 | 6 | 41 |

Appendix: Errata

Errors in Feb 13 response to AEC

First, in the section "The AEC’s membership test methodology artificially reduces sample size":

Keep in mind that – given this experimental setup – we’d expect 9 or more failures 10% of the time. If we were doing this experiment in real life, 10% of the time we would underestimate the number of cars by a factor of more than 2500x.This is a typo -- we'd expect 8 or more failures 10% of the time, and 9 or more failures ~5% of the time.

Second, in the section "Closing remarks":

Consider a soon-to-be-registered party with 1650 valid members (assume this is true). What happens if 200 malicious members join (prior to registration), with the sole purpose of preventing that party from registering? Then, it’s expected that ~10.8% of the membership list provided to the AEC as part of their registration application are these malicious members. Thus the failure rate according to the AEC’s methodology is expected to exceed the current threshold (set by the AEC) – the AEC would conclude that the party does not meet requirements.The italicized part is not correct. The AEC's method is much better than this -- it only fails 10% to 20% of the time (the above quote implies that the method fails more than 50% of the time). The exact false negative rate depends on the number of members filtered by the AEC, similar to how our December 2021 list of 1649 names had 24 entries filtered. The AEC's method is more reliable when fewer names are filtered, with the 20% false negative rate corresponding to 25 members filtered out. (0 names filtered corresponds to a 10% false negative rate.)

It is worth pointing out that there are similar (though slightly more extreme) parameters that do result in a >50% failure rate of the AEC's method. For example a party of 2000 members, 300 of which are malicious, and 15 names filtered has a failure rate of 50.4%.

Note, there are some other errors too, like the method mentioned in the The AEC’s membership test methodology artificially reduces sample size section uses the random sampling size that was used in Flux’s test, but it probably should have been 60 instead of 53. Not really a big deal.

Use of “confidence” in prior versions

In some prior versions of this document, the term “confidence” was used instead of “accuracy”. That is: it was used to describe how often the AEC’s test arrived at the correct result.

![]()